On Saturday 8th July, I travelled up to Macclesfield to attend researchEd Cheshire. I had a really great time at the event, met some lovely people and had some fascinating conversations. Meeting Dame Alison Peacock was a real highlight, and I was delighted to share my research ideas with her. I also met so many people who I have only ever ‘met’ on Twitter, and it was great to finally meet in person and share ideas.

I wanted to summarise my talk here, as I have been asked for my reference list (which I am very happy to share at the end of this post). I haven’t added my slide deck in full as I have some results and findings that I used to illustrate some of my points, which I need to keep ‘in the room’ until I write my thesis up. I will try to give you the gist of my ideas and findings in this post, though. I’m also going to share my ‘journey’ to this point. I hope this puts my study in context, and perhaps inspires you to start further studies or action research of your own!

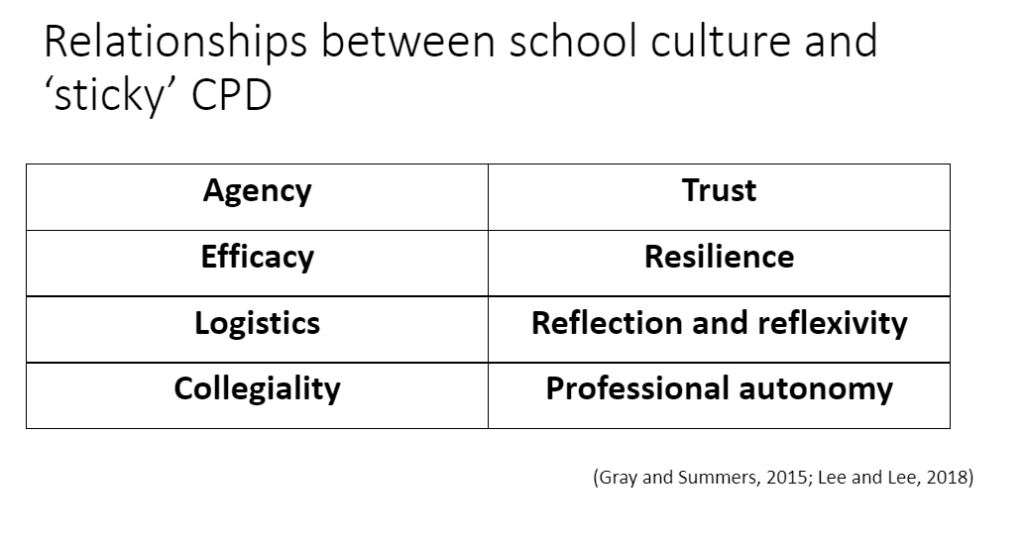

My thesis research focuses on the relationships between school cultures and teacher professional development and learning. I make the distinction between professional development as activities and learning as changes in attitudes and practices, as McChesney and Aldridge (2019) do. I think this makes it easier to talk about what is going on in this area in a clearer way.

My research is exploratory and interpretative in nature. This is important because I don’t intend to give an impression that I have discovered a generalisable ‘fix’ that might be picked up and parachuted in to any school, anywhere. That said, I hope that the survey instrument that I have developed provides a useful mechanism by which teachers and school leaders can reflect on the cultural conditions which are most associated with positive teacher attitudes to their professional development opportunities.

Professional learning

There are a couple of things about teacher professional learning that I hold to be true, and which are supported by literature in the field. Firstly, we should expect teacher professional learning to be an ongoing process. I work with Early Career Teachers, and I love it when they express their hunger for professional development opportunities. I like Hargreaves and Fullan’s (2012) analogy to illustrate this point. ECTs are like the best band on a Saturday night in the local pub; they’re talented, they’re enthusiastic, they’re up for it. They’re great! But we all need to be engaged in a career long endeavour to get to the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury (or the O2, if you prefer, although there are definitely times in teaching where an analogy associated with wading through mud works…)

Secondly, there is so much interesting research out there, in all of our fields of professional interest that simply wasn’t written when we trained. More is published every year. Some in journals, some in accessible books. Podcasts and bite-sized chunks on blogs and a great way to connect with all kinds of ideas. You don’t have to use it all, but it’s worth engaging with (in a discerning, research-savvy way).

Professional Identities and Paradigms of Professionalism

Teacher professional identities are important in shaping us on our journey. The chances are, your professional formation started when you were at school yourself. It is an ongoing, adaptive process. It is underpinned by our (often implicit) understanding of the competing concepts of teacher professionalism. These provide a useful lens to view our professional identities through. I have discussed in previous posts the paradigms of teacher professionalism: managerialist (measure and standardise teacher activities), traditionalist (keepers of special knowledge and skill not available to lay people; experience = expertise), and democratic (seeking to make skills and knowledge explicit, and de-mystify teacher professional activities; research engaged). I find it helpful to think about these when trying to understand and explain why some things seem to happen as they do. (I have blogged about this before, with references. Please see https://cultureinsights.blog/2023/05/27/professional-paradigms-at-dawn/ for details).

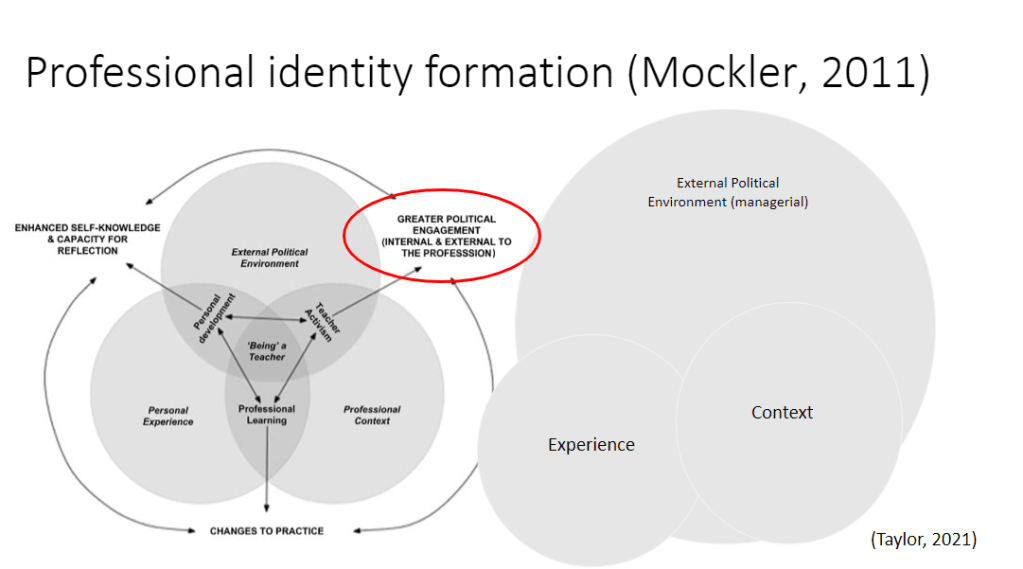

These paradigms are not always compatible (arguably, they can be incompatible), and this leads to tensions. To illustrate this, I turn to Mockler’s (2011) model of the influences on teacher professional identity formation. This model places teacher professional identity at the centre, between external forces of equal influence and magnitude (first image). However, I argue that the ubiquity of the managerialist paradigm means that all of our context and experience is influenced by it (second image).

Both Mockler (2011) and Buchanan (2015) share concerns that engagement with research evidence and political activism/awareness (implicitly in the form of democratic professionalism) are essential if teachers are to avoid being subsumed into the managerialist paradigm. We’ll be like the fish asking what water is, not recognising it as a substance that surrounds us.

Democratic professionalism offers a mechanism for being aware of fresh ideas. In this sense, teachers who identify with democratic professionalism may be disruptive, as they question and challenge the status quo. I don’t think this is a bad thing, by the way. Discussion, innovation, collaboration and review are all really good ways of making things better. But it is not always an easy or comfortable path. However, this process can also empower teachers and offers protection from some of the effects of burnout (Sullanmaa et al., 2023). In my view, this is preferable to the alternative, in which the system just grinds you down and burns you out. If you tend towards the traditional paradigm you may experience managerialism as oppressive (and it certainly has been implemented in ways that cause toxic and performative cultures). This tends to result in burnout as your perception of agency and autonomy are eroded. When you feel like you have limited agency, what to do but resist your professional development and your line manager (Ball, 2016; Taylor, 2021)? Short of leaving the profession, resistance is the refuge of those who feel their professional agency being systematically dismantled.

Seeking Solutions to My Problems

Into this context, I formulated my research project. Before I explain, I will give a bit of personal context. In May, 2018, just before half term, I was ready to walk away from teaching. A number of issues had pushed me to the point of crying in my car and working out my financial bottom line on the backs of envelopes. As I contemplated a May 31st resignation, another alternative occurred to me: an EdD. One of my professional frustrations concerned how EdTech was being used in my school. We had a marvellously clever learning platform, and we were using it as a diary. No-one seemed to have the capacity to explore the functionality beyond the basics. I said it would save people time and reduce workload. Many colleagues said they couldn’t afford the time to learn how to use it. I applied to the IoE at UCL with the intention of ‘proving’ (how naïve!) that EdTech could improve student outcomes and reduce teacher workload. Job done.

Except that wasn’t really what the problem was. The EdD at the IoE begins with a taught programme that focuses on the conceptualisation of professionalism that I outline above. I felt as though the scales had fallen from my eyes. I went though many emotions, including anger. I came to realise that not only was it ‘not me’ (car crying, bottom-line calculating me), it was The System. Worse, what I had experienced was well documented over a period of at least 20 years. I marched around school with my heavily annotated copy of ‘Flip the System’ (Rycroft-Smith & Dutaut, 2018) like the worst kind of born-again evangelist. After a time, I settled down and decided to understand the issue better, and try and make a contribution to finding a solution. This is how I came to begin to explore the cultural conditions that promote teacher professional learning.

Culture Insights

What follows are some of the insights I have discovered as I have progressed though my studies. Firstly, I identified some concepts that, when perceived strongly by teachers, seem to promote openness to professional development activities. I then began to investigate how these concepts were understood and used by teachers. My Impact article explains more about this process.

After months of research, analysis, testing and re-design, I have developed a survey instrument that can tell teachers and school leaders how they perceive their school cultures. This reveals things like the need for flexibility, as the pinch points start to show up around the 9-15 years in service mark, when large numbers of teachers appear to feel that their schools don’t support their career and life stages. It shows up teachers who struggle to get meeting rooms, or find time to collaborate; teachers who want to support colleagues (but as the mentor, not with a coach), and those who would love to find an effective coaching relationship. It reveals teachers who trust their own judgement, but experience inconsistent line-management arrangements (too tight or too loose, not always a good balance of support and challenge). There are teachers who would love more praise and those who want to be left alone. It reveals so much about how teachers experience their school cultures. I think it indicates how open teachers are to their professional development opportunities.

Importantly, engaging with the survey provides a cultural artefact which can be used to prompt fruitful discussion from which positive changes can be negotiated. I think reflection is healthy and beneficial, and an exercise in professional development in itself.

My work is still ongoing. My hunch is that, where schools have paid deliberate attention to a professional development curriculum for teachers, the general perceptions of these cultural factors is increased. I am looking forward to exploring this idea further.

References

Ball, S. J. (2016). Subjectivity as a Site of Struggle: Refusing Neoliberalism? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 37(8), 1129–1146. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1044072

Buchanan, R. (2015). Teacher Identity and Agency in an Era of Accountability. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 700–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044329

Gray, J. A., & Summers, R. (2015). International Professional Learning Communities: The Role of Enabling School Structures, Trust, and Collective Efficacy. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(3), 61–75.

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. Teachers College Press. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3545010

Lee, D. H. L., & Lee, W. O. (2018). Transformational Change in Instruction with Professional Learning Communities? The Influence of Teacher Cultural Disposition in High Power Distance Contexts. Journal of Educational Change, 19(4), 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-018-9328-1

McChesney, K., & Aldridge, J. M. (2019). What Gets in the Way? A New Conceptual Model for the Trajectory from Teacher Professional Development to Impact. Professional Development in Education, 0(0), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1667412

Mockler, N. (2011). Beyond ‘What Works’: Understanding Teacher Identity as a Practical and Political Tool. Teachers and Teaching, 17(5), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.602059

Sullanmaa, J., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2023). Teacher Agency in the Professional Community and Association with Burnout: A Longitudinal Person-Centred Approach. Research Papers in Education, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2023.2178028

Rycroft-Smith, L., & Dutaut, J.-L. (Eds.). (2018). Flip the System UK: A Teachers’ Manifesto. Routledge.

Taylor, K. (2021). Where Teachers Meet the State: A Battle for Professionalism? A Qualitative Exploratory Investigation into Experienced Secondary School Teachers’ Perceptions of the Relationships Between Their Professional Identities, Organisational Coupling, and Professional Development and Learning. [IOEF0001: Institution Focused Study 2020/21]. University College London. Unpublished EdD assignment.

Leave a comment