Structure and protocols are needed for groups to work productively together, both promoting individual and group learning (Crome, 2023), and this was reflected in my EdD data (Taylor, 2025). Teachers in all five of the schools in my study appear to value opportunities to collaborate productively, understand their place in the system and make efficient use of their time for the best possible outcomes.

Here, I present my analysis of school leaders’ and teachers’ qualitative comments relating to teacher preferences concerning PD. Leaders had more input here, having been asked directly during qualitative interviews, however, I also included teachers’ qualitative comments in my analysis.

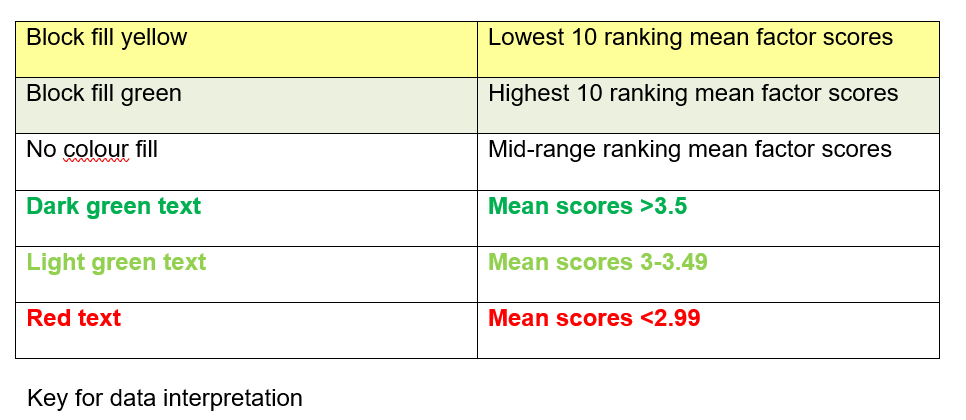

Structural barriers inhibiting PL were ubiquitous, always appearing amongst the ten lowest scoring factors. As noted above, work-life balance is a wicked problem. Growing teacher demands for flexibility, including part-time working patterns, are challenging for poorly resourced and economically restricted schools. Weak E7: Invested belonging is often associated with weak L3: Collaborative research, highlighting the importance of logistical support for PD2.

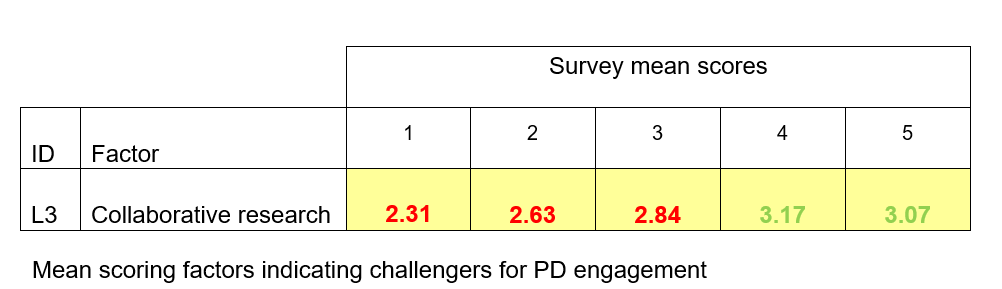

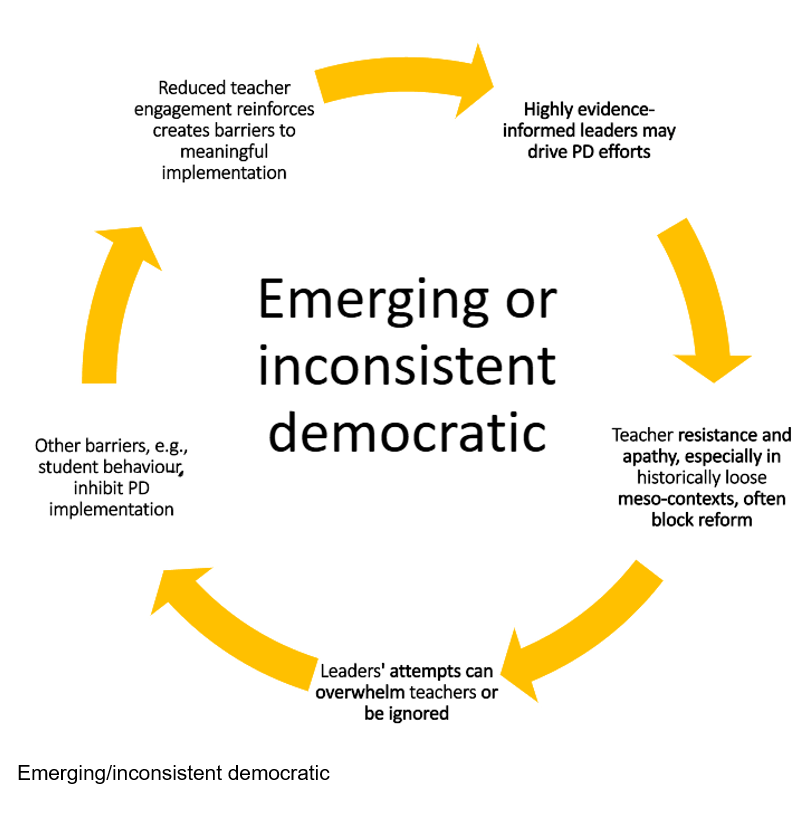

Workload emerged as a key issue for leaders, influencing PD planning decisions. Structure was imposed to varying degrees to promote teacher engagement. Depending on leaders’ beliefs and assumptions about teacher professionalism and autonomy, and school priorities, the signposting of PD1 strategies and knowledge were held as efficacious. A tentative typology emerged from the cross-case analysis:

- Loose democratic

- Moderate/inconsistent democratic

- Tight democratic (distinct from tight managerial, which is often experienced as micromanagement)

The following accounts are drawn from multiple schools, conflating elements of similarity for heuristic effect. I have visualised each cyclically for clarity, however these are an over-simplification. Real-world situations are dynamic and complex. Schools and the people within them are subject to myriad pressures and demands and must be reactive as well as strategic in their PD provision. All plans and actions in social systems are subject to unintended consequences. Thus, I do not suggest that such characterisations are predictable, directly cyclic or linear. Indeed, they are likely to be temporary and conflated within organisations, and different individuals may find that different patterns resonate under different circumstances within different departments and at the whole-school level. Rather, I aim to ‘sketch’ dynamics within school PD provision which are recognisable to teachers and leaders in the spirit that they might prompt reflexivity to disrupt unconscious and unwanted patterns of behaviour in their schools.

In systems characterised by loose democratic PD provision, leaders want evidence informed teaching and learning, but workload concerns prevent tight PD arrangements. Low teacher engagement with voluntary PD is a persistent frustration. Two consequences are associated with loose arrangements. Firstly, PD1 (the content/theory/practice which is to be delivered) is often transmissive, and experienced by some teachers as a de-facto deficit model (Kennedy, 2014). Lacking PD2 contextualisation (structured, logistically supported opportunities for discussion, action research and co-creation, upon which deep understanding and sustained learning depends), teachers experience PD as infantilising, generic or irrelevant.

Secondly, despite leaders’ explicit intentions to trust teachers’ autonomy according to their professional judgement, the laissez faire approach to PD implementation contributes to tacit sub-cultural counter-narratives. For instance, teachers are trusted and left to get on with the job (which some undoubtedly want), but the absence of micro-affirmations demotivates others (Taylor, 2021). Teachers experience frustration if their experience or qualifications are overlooked, diminishing feelings of belonging. Further, concern over teacher practices is communicated only after student or parental complaints or falling results. Commenting on responses to occasional teachers’ negative reactions to whole school CPD, one leader pragmatically accepted that some teachers would not wish to change their practices. Low-level teacher disengagement with PD was tolerated, unless other concerns arose with their practice or results. Conversations of that nature were delegated to line managers using the school’s annual performance review procedures:

“[Negativity about PD would only be a problem] if what was going on in the classroom was concerning. You can’t… [force them to engage with PD]. Ultimately, we want the drive for CPD and professional learning to come from the staff member themselves… [We would use] the appraisal process and a conversation with the line manager who can talk openly about CPD, I think.”

Leader, school 1

Evidently routine appraisal and target setting risks becoming conflated with corrective leader interventions. This approach may risk undermining teachers’ trust of line managers because some teachers may experience intervention as corrective, not developmental. Loose coupling arrangements are associated with minimal managerial intervention, meaning that teachers may not expect intervention from their line manager when things were going well. Thus, when challenged following a crisis, teachers may feel their practice is ‘suddenly’ problematic after being ‘fine’ for many years. Loose democratic coupling rests on assumptions that PL will occur naturally under radically autonomous conditions following PD1 delivery, but this laissez-faire approach has unintended consequences. ‘Ruinous empathy’ in leader/teacher interactions allowed under-performance to ‘drift’ unless a crisis occurred (Scott, 2017), undermining teachers’ trust in leaders, constituting a PL barrier (Schein, 2017).

Poor communication about PD exacerbated teachers’ frustrations, tacitly implying its low priority. PD content agendas may not be published, causing confusion. If PD sessions are cancelled (sometimes at short notice), time may be released for mandatory online training, serving dual purposes of training and compliance monitoring. Online training is experienced as physically isolating and annoying those who had arranged childcare to enable them to attend in person PD.

Emerging or inconsistent patterns of PD provision are associated with highly evidence informed and research engaged leaders. Leaders’ formal qualifications (such as an NPQ or a Master’s degree) may provide a springboard for PD revival efforts. Teacher resistance and apathy can become barriers to reform. Although leaders’ attempts to implement evidence-informed strategies may be coherent, they may be inhibited by logistical challenges and/or historic loose meso-contexts. Here, Baron’s leader challenged the stereotype of disengaged experienced teachers having experienced significant resistance to structured PD interventions from ECTs after covid, which halted most PD activities:

“We have a slightly higher proportion of UPS3 teachers, but we’re pretty evenly spread […] There was a cluster of ECTs who had only been here at a time when there wasn’t effective CPD [during Covid]. So, we had some resistance to [our new CPD] because they had never had experience of professional development, and I saw, broadly speaking a greater degree of acceptance and enjoyment from [experienced] colleagues who have worked in other schools. So, there wasn’t the traditional curmudgeonly stereotype.”

Leader, school 2

This was an interesting reflection because it points to the importance of routines, structure and expectations around PD arrangements in schools; socialisation into what is expected or normalised in a school seem to play a role in teachers’ attitudes towards and willingness to engage with PD. This supports Giddens’ (1984) view that structuration facilitates reflection and change through cycles of artefact generation and collegial examination which drive incremental changes in practice and the wider organisational culture.

Depending on leaders’ status and influence they may feel empowered, or perhaps overwhelmed. For the leader at school 3, their Master’s degree had caused them to reflect on the complexity of developing PL-supportive conditions. They were moving from unconscious to conscious awareness of organisational change dynamics, and the limits of their, and their colleagues’ understanding (Kruger and Dunning, 1999):

“Some people are starting where I’m starting and there are some people who are starting 1,000,000 miles away and I don’t necessarily want to bring them towards me, but I think they need to understand what we mean by professional learning and then look at the evidence […] what research shows us leads to better outcomes.”

Leader, school 3

Such awareness and reflexivity are an important aspect in leaders’ development of their ability to affect and sustain the changes they seek (Earley and Bubb, 2023). Without this kind of self-awareness and introspection, leaders’ fervour may ‘shock’ and overwhelm teachers into inaction and resistance, or their efforts may simply be ignored, leaving leaders disempowered and frustrated (Schein, 2017). Application barriers to teacher PL, such as poor student behaviour further inhibits teachers’ PD engagement (McChesney and Aldridge, 2019).

Embedding a democratic, evidence informed school PD culture takes time and effort to establish. This results in a ‘tail’ of incongruent teacher perspectives during implementation. Leaders mitigate this by communicating a clear vision in which research informed PD engagement constitutes a professional expectation. Tight democratic differs from tight managerial because of the explicit collegial exploration of pedagogical strategies and contextualisation, as opposed to managerial diktats. In the following comment. School 4’s leader for PD describes the process of taking an intervention from research-evidence to policy through a process of deliberate school-based action research and contextualisation. Here, having identified a promising teaching and learning strategy, teachers are given time to explore and contextualise those strategies in their departments. Following this co-creative process, adaptations to the strategy were integrated into the school’s teaching and learning policy:

“[…]100% [teacher] autonomy with no teaching and learning policy [and] no understanding of best bets wouldn’t be right. So when the things have been hit upon through teaching and learning teams become policy, our staff are already aware of it and lots of the staff are doing it already and it’s already been talked about in collaborative planning time and therefore it’s not a surprise… we have buy in because people know they’ve been part of, or have the opportunity to be part of a consultation process. […] we [start from] a credible [research-informed] source [which] sits alongside trials from our school, in our classrooms, in our context, with our staff, our students, our subjects. and I think that’s really important.”

Leader, school 4

Thus, staff input plays an integral role in policy development, supporting the acceptance and sustainability of interventions.

In tightly democratic school contexts, core and interest-driven pathways are provided, but all must engage with something. Coaching is mandatory. To use Stenhouse’s (1991) analogy, teachers may choose what moves to make on the chess board, but everyone is expected to play. My data suggests that the tight democratic pattern is associated with the highest quantitative mean survey scores associated with high congruence: most teachers experience their school culture for learning positively, and there are few outliers. This indicates a correlation between teacher openness to PL and tightly curated democratic conditions characterised by structurally supported mandatory (or at least high voluntary) engagement with PD2, implemented at a manageable pace over time. Organisational belonging and pride (understanding universal acceptance is an impossible ideal) is also indicated. Leaders should remain mindful of problems of comfort and ambition, however, as it is desirable for organisations to allow some un-curated ideas into their PD ecosystems to avoid groupthink (Epstein, 2019).

My data analysis suggests teachers’ open-mindedness to learning, indicating that teachers’ PL capacity poses a greater threat to PL than their disengagement or rejection of PD content. My analysis suggests relationships between PD2 structures, which support contextualisation, co-construction and meaning making of interventions, and teacher PL. Deliberate planning to incorporate PD2 allows provisional ‘best bets’ to become espoused values and embedded practices, and guards against practice dogmatism. Structuration theory (Giddens, 1984) and lessons from the business world (Schein, 2017) support the importance of such collegial learning opportunities as well as providing, through structuration processes, a mechanistic explanation of how theory can be used to steer and curate changes in practice.

References:

Crome, S. (2023). The Power of Teams: How to Create and Lead Thriving School Teams. S.l.: John Catt.

Earley, P. and Bubb, S. (2023). ‘Understanding What Makes School Leaders Effective: The Importance of Personal Development and Support’. in International Encyclopedia of Education(Fourth Edition). Elsevier, pp. 393–400. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818630-5.05005-3.

Epstein, D. J. (2019). Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. New York: Riverhead Books.

Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Polity Press.

Kennedy, A. (2014). ‘Understanding Continuing Professional Development: The Need for Theory to Impact on Policy and Practice’. Professional Development in Education, 40 (5), pp. 688–697. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.955122.

Kruger, J. and Dunning, D. (1999). ‘Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77 (6), pp. 1121–1134. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121.

McChesney, K. and Aldridge, J. M. (2019). ‘What Gets in the Way? A New Conceptual Model for the Trajectory from Teacher Professional Development to Impact’. Professional Development in Education, 0 (0), pp. 1–19. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1667412.

Schein, E. H. (2017). Organizational Culture and Leadership. 5th Edition. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Scott, K. (2017). Radical Candor: How to Be a Great Boss Without Losing Your Humanity. First published. London: Macmillan.

Stenhouse, L. (1991). An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development. London: Heinemann (Heinemann educational books).

Taylor, K. (2021). Where Teachers Meet the State: A Battle for Professionalism? A Qualitative Exploratory Investigation into Experienced Secondary School Teachers’ Perceptions of the Relationships Between Their Professional Identities, Organisational Coupling, and Professional Development and Learning. IOEF0001: Institution Focused Study 2020/21. University College London.

Taylor, K. (2025). Developing an Ecological Analytical Framework for the Exploration of Teachers’ Lived Experiences of Professional Development and Professional Learning in Five UK Secondary Schools. IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society, UK.

Leave a comment